Автор статьи Регина Хидекель, член Международной Ассоциации арт критиков, создатель и директор Русско-американского культурного центра в Нью-Йорке, президент Общества Лазаря Хидекеля.

https://russianamericanculture.com

https://www.lazarkhidekel.com/

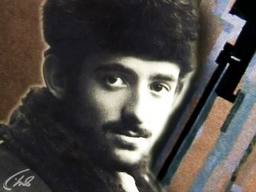

Лазарь Хидекель – траектория супрематизма – между небом и землей

Go to english version

[quote style=”boxed”]От шагаловского метафорического взлета над знакомыми с детства улочками было уже рукой подать до систематизированных полетов в бесконечных пределах супрематического пространства. «Отмененные» Малевичем ренессансная перспектива и линия горизонта, открыли другое пространство – бескрайний космос, который стал той плоскостью, на которую Лазарь Хидекель проецировал свои супрематические композиции. Здесь, между небом и землей, преодолев гравитацию, в безвесии формировались геометризованные структуры, которые прежде чем превратиться в приподнятые над землей объемы городов будущего, дрейфовали в статусе космических станций землян.

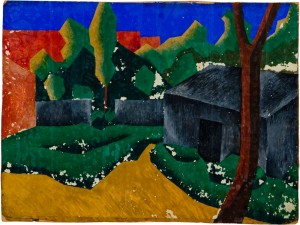

Дворик в Витебске. 1919

Именно эта траектория развития супрематизма ввысь, в космос, а потом возвращение на землю, с остановкой в надземных городах будущего — определила путь формирования художественного и архитектурного супрематизма Хидекеля.

Благодаря уникальности сохранившегося обширного архива Лазаря Хидекеля, каждый период его искусства строго документирован художественными работами, документами, публикациями, а также рукописями и статьями самого художника. По архиву можно изучать процесс обучения супрематизму в витебской художественной школе и Уновисе, включая раннюю подготовку Лазаря Хидекеля – художника, получившего графическое мастерство в классе Мстислава Добужинского и живописное непосредственно под руководством Марка Шагала (1918), основы архитектурного черчения и проектного мышления в архитектурной студии Лисицкого (1919-1920), и индивидуально обучавшегося супрематизму в «Динамической» студии Казимира Малевича (где, согласно уновисовской анкете, он был единственным учеником).

Также, благодаря открытию архивов Гинхука, ГИИИ и публикации наследия Малевича, появилось большое количество документов, подтверждающих огромную роль и значение Хидекеля в развитии супрематизма. Он быстро включился в систему супрематизма, в то время как большинство студентов никогда не сумели перейти порог беспредметности. Их было всего четверо –Чашник, Суетин, Червинка и Хидекель, которого Чашник в одном из своих писем назвал «революционным супрематистом». 2/ Как отметила Шарлота Дуглас, один из первых и наиболее значительных американских исследователей супрематизма, ученики шли дальше и развивали супрематизм в разных направлениях. «Различие (от других учеников – Р.Х.) было только в том, что это изначальное видение плывущих в пространстве супрематических структур осталось центральной частью и оплодотворило все дальнейшее развитие искусства и архитектуры Хидекеля на ближайшие сорок лет». 3/

Во второй половине 1920х, когда Малевич вернулся к переосмысленной супрематизмом фигуративной живописи, Хидекель продолжал свою космическую одиссею в облаках футуристических городов; что еще более существенно, он единолично продолжал развивать живописно-пространственные идеи супрематизма в течении всей своей жизни, предвосхищая возникновение многих авангардных идей и направленией в западном искусстве, дизайне и архитектуре, от которых он был отделен «железным занавесом».

Если доклад С.О. Хан-Магомедова в 1977 году о городах будущего Лазаря Хидекеля 4/ вызвал скептическое отношение некоторых его коллег, которые высказались в том сысле, что если Хидекель опередил Иону Фридмана и японских метаболистов 1950х годов, то он гений, сегодня гениальность Хидекеля подтверждается словами самого Малевича. В конце февраля 1927 года перед отъездом за границу, он оставляет наказ относительно работы над «супрематической фильмой»: «Нужно, чтобы Хидекель сделал архитектур<ный> план, если не успеет, то у Петина пусть возьмет свой снимок для дачи зас<ъ>емщикам. Нужно показать все развитие объемного Супрематизма> по ощущениям аэровидного, динамич<еского>…». 5/ В годы между 1925 и 1932 Хидекель создает свои основные концепты аэро-городов, городов на опорах, над водой и в воздухе.

Проекты городов будущего были не только у Хидекеля, но и других художников, в том числе, из круга Малевича. Чтобы увидеть различие, достаточно вспомнить социальную графическую утопию Клуциса – “Динамический Город ”( 1922), город -планета, «воздвигнутый руками рабочих людей», чьи фигурки «засняты» в момент рабочего движения» 6/ . Хидекель же если и помещает в свои архитектурно – графические листы фигуру, то как правило, самого себя, и обязательно пейзаж.

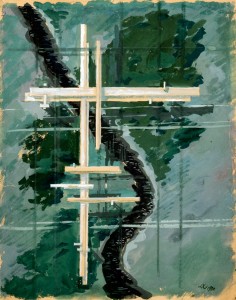

Аэрогород Хидекеля был сомасштабен человеку и даже в сер. 20-х инженерно осуществим, предлагая гуманный путь развития цивилизации, гда забота об индивидууме и природе равноценно важны. Хидекель верил, что человек и есть природа, и что природа и человеческая культура управляемы теми же законами естественно-природных сил.

Благодаря присущей с детства обращенности к звездному небу, шагаловскому старту и пониманию супрематизматической конструкции как живого саморазвивающегося организма, планетарное видение Лазаря Хидекеля навсегда сохранит теплоту и человечность, а его живописно-архитектурные эскизы городов будущего с преобладанием разных оттенков зеленого, мастерски выраженных художником, свидетельствуют о введении им нового измерения архитектурного творчества – экологическом, увы, редком для футуристических утопий, а чаще фантасмагорий 20 века, да и его далекой от гуманизма реальности.

Один из студентов Хидекеля вспоминает, что профессию архитектора он считал доброй, защищающей человека.

Один из студентов Хидекеля вспоминает, что профессию архитектора он считал доброй, защищающей человека.

Воздух и лучи солнца были критериями архитектурного сооружения, о чем Хидекель пишет в одной из первых опубликованных профессиональных статей «Плоские крыши», где приводятся технологичикие и экономические доводы для внедрения горизонтального зонирования. «Необходимо отметить, что плоская крыша, дающая добавочную площадь, овеваемую свежим воздухом и освещаемую солнечными лучами, оправдывает себя в экономическом отношении» 7/, пишет молодой архитектор, озабоченный санитарно-гигиенической ситуацией современных городов.

О преодолении противоречий между природой и цивилизацией Хидекель говорит уже в своем первом манифесте. В 1920 году, 16-ти летний Лазарь Хидекель совместно со своим товарищем по Уновису Ильей Чашником, выпускает «АЭРО. Статьи и Проекты» 8/, одну из первых публикаций Уновиса, предвосхитившую выпуск «34 рисунков» Малевича в тех же литографических мастерских Витебской школы 9/. «АЭРО» вошел в историю современного искусства как первый экологический манифест. Сам термин станет знаковым в искусстве Хидекеля, отразившимся в пространственном моделировании от космических поселений, туманоидов, аэрогородов (также термины Хидекеля) до планировки реальных зданий и живописных фантазий.

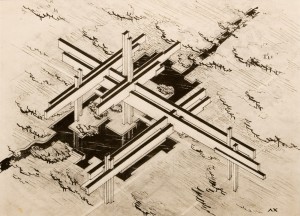

[quote style=”boxed”]Уже в 1922 году объемная аксонометрия Хидекеля в форме самолета будет названа им Аэроклубом.

Относительно этой «первой подлинно архитектурной копозиции на базе супрематизма», Хан-Магомедов задается вопросом: почему Хидекель обладал архитектурными навыками, которые позволили ему построить «диаметрическую аксонометрию (т.е. по одной из осей размеры сокращены в два раза), что раньше не встречалось в объемном супрематизме» 10/ . Он находит ответ в том, что поступив в 1922 в ПИГИ, «Хидекель проходит курс профессионального обучения, и оставаясь при этом сотрудником ГИНХУКа он помогает не умевшим строить перспективу Малевичу, Суетину и Чашнику выполнять архитектоны и планиты.» 11/

Л. Жадова также отмечает, что: «Главным помощником Малевича в архитектурных экспериментах в 1924-1925 годах был Л.М. Хидекель» 12/.Согласно документам ГИНХУКА, Хидекель руководил лабараторией супрематической архитектуры, составлял программы и оставил уникальное описание самого помещения лаборатории и находящихся там моделей.13/

Лицо архитектурного супрематизма определил Хидекель, в 1926 году создавший первый, ставший сенсационным, проект реального супрематизма – «Рабочий клуб», который был мгновенно опубликован на страницах западных, а затем и отечественных журналов. 14/ Известность архитектора Хидекель обретает будучи студентом – явление еще более беспрецедентное, нежели его ранние выдающиеся достижения в искусстве, включая участие в 15-летнем возрасте в выставке наряду с ведущими мастерами эпохи, Кандинским, Шагалом, Родченко, Поповой, Экстер15/.

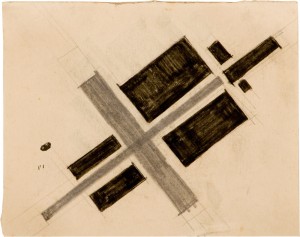

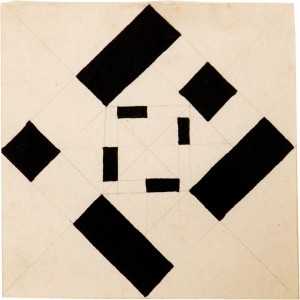

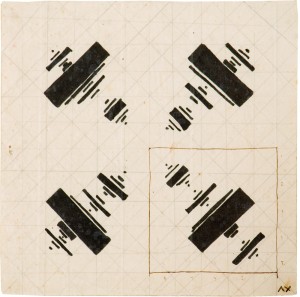

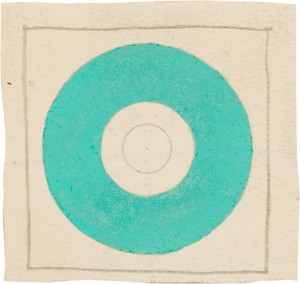

Этапы в космос и в объем следовали друг за другом, выявляя формообразующие потенции супрематизма – так образовался некий крестообразный композиционный каркас, ведущая диагональная ось котрого – силовая линия, определяла направление движения. Одним из решений была композиция «Рассечение черного квадрата», которую Хидекель относил к группе работ, включая туманоиды, концентрические круги, решетку, летящие космические станции, которые он считал своим вкладом в формообразующую систему супрематизма.

Это постижение беспредметного пространства средствами универсальной системы геометризации осуществляется в особой графической монохромии, манере, отличной от еффектной цветовой супреграфики Суетина и Чашника тех лет, а скорее предвосхищающей язык компьютерных визуализаций.

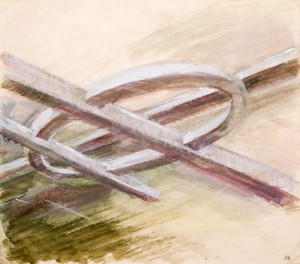

Диагональные центричные композиции начала 20х стали стартовой площадкой для выхода живописного супрематизма в объемно-пространственную среду, а диагональ как ось движения, взлетная полоса стала важнейшим композиционным элементом, который мы вновь встретим у Хидекеля в конкурсных проектах 1950-60х музея Циолковского и Будапештского Театра, в индустриальных проектах (параллельно с преподаванием в ЛИСИ Хидекель работает в ГИПРОМЕЗе), в проектах учеников, которые с гордостью относят себя к «школе Хидекеля», в живописно-пространственных фантазиях, которые предназначались для гигантских плоскостей современных сооружений.

[quote style=”boxed”]Хилтон Крeмер в своей рецензии на нью-йоркскую выставку 1995 года 16/ пишет, что более всего его поразили работы Лазаря Хидекеля, чьи маленькие абстрактные «Супрематические концентрические круги» 1921 года поразительно напоминали эскизы к очень похожим полотнам Кеннета Нолланда, сделанным много лет спустя.

Крамер не знал, что концентрические круги Хидекеля – это тепловые пояса, расходящиеся от ядра земли, о чем нам говорят его поразительные рисунки с комментариями 1920-1922 годов. Тончайшая разно-фактурная пастельная палитра шедевра «Концентрические круги» 1921 г. связана с монохромными туманоидами и космическими структурами, но также соотносится, как в случае с Ноландом, с направлениями минимализма и живописи цветового поля (color field painting), возникшими спустя десятилетия.

Сегодня, когда «АЭРО» по праву вошла в таймлайн современного искусства 17/, стало ясно, что свей радикальностью она резко отличается от известных нам рукотворных футуристических книг: произведение искусства определяется как проект и сопровождается машинописным текстом; не в этом ли стремлении связать искусство, науку и философию лежат истоки концептуализма?

[quote style=”boxed”]В работах Лазаря Хидекеля прослеживается логика развития авангардного искусства 20-21 веков.

Круги Кеннета Нолланда. Окраска в синий цвет фигуративных монументов 1940х годов, предвосхитившая синие бюсты Ива Клейна. Органические формы «супрематизма» Захи Хадид могут быть соотнесены с органическим формами приподнятых на опорах городов будущего Хидекеля, где прямоугольные углы неожиданно округляются и возникает остро современная аэродинамическая конфигурация (серия рисунков вт. половины 1920х гг.) Создавая свои пространственно-живописные фантазии в середине 1950-1960 х годах, Хидекель предвидел увеличение размеров современных живописныых полотен. Он говорил, что человек 19 века был пешеходом и мог рассматривать детали, в веке скоростей – на автомобилях и из самолетов будут доминировать объемы, и размер полотен как отражение видимого пространства во времени соответственно увеличится.

[quote style=”boxed”]Лазарь Хидекель принадлежал к ядру той группы художников, которым удалось вырваться из одного времени в другое, из внутреннего земного пространства во внешнее, космическое, что вот уже второе столетие дает неисчерпаемые возможности открытия новых миров в искусстве.

1/ Архив семьи Хидекеля

2/ Письмо Чашника Хидекелю от 22 мартf 1922 г. Архив семьи Хидекеля

3/ Шарлота Дуглас «Неземное искусство: Планетарное видение Казимира Малевича и Лазаря Хидекеля», 2011, статья для готовящейся к изданию книги «Лазарь Хидекель (1904-1986). Супрематическое видение мира».

4/ О.С.Хан-Магомедов «Лазарь Хидекель» М., Фонд «Русский Авангард», 2008, с. 24

5/ «Малевич о себе. Современники о Малевиче.» Вакар И.А., Михеенко Т.Н. (сост.) Издательство: «RA», с. 150

6/ О.С.Хан-Магомедов «Супрематизм» M., Фонд «Русский Авангард», 2007, с.310

7/ Лазарь Хидекель «Плоские крыши», «Наука и техника», 1928)

8/ Лазарь Хидекель и Илья Чашник «АЭРО. Статьи и Проекты» 1920, Витебск, Уновис

9/ Лисицкий одновременно с архитектурной руководил также мастерской печатной графики, что сподвигнуло Хидекеля и Чашника создать их первую книжку «Аэро». Хидекель также участвовал в процессе издания «34 Рисунков», о чем свидетельствует подписанный им оригиналный вариант книги. Архив семьи Хидекеля

10/ О.С.Хан-Магомедов «Супрематизм», с.473

11/ там же, с. 473

12/ Л. Жадова «Супрематический ордер» – «Проблемы истории советской архитектуры», М.,1983, с.37

13/ Публикация Ирины Карасик для готовящейся к изданию книги «Лазарь Хидекель (1904-1986). Супрематическое видение мира».

14/ Студенческий проект Л. Хидекеля «Рабочий клуб» был опубликован в: Wasmuths Monatshefte fur Baukunst”, Berlin, 1927, p. 413; “L’Architecture Vivant”; Paris, 1928, v. II, p.46; Современная Архитектура, М., 1927, No 6 и 1930, No 4, и десятках журналов и книг

15/Первая государственная выставка местных и московских художников, Витебск, 1919

16/ Hilton Kramer, “Jewish Artists in Rubble of Tragic Russian Era”, New York Observer, 2 октября 1995, c. 1

17/Выставка «100 лет конструктивизма» в Музее Хауз Конструктив, 2010-2011, Цюрих, куратор – директор музея Др. Доротеа Штраус

Lazar Khidekel: The Trajectory of Suprematism; Between Sky and Earth

Back to the top

The cosmic “gene” of Suprematism, the philosophy of Russian Cosmism in Malevich’s interpretation and his cosmological concepts, fell on fertile ground. The adolescent, who, by his own account, “walked the streets late at night, staring at the sky, the moon, and the clouds waiting for the coming of the Messiah, who (…) appeared floating in the clouds of the dark sky,”1 soon encountered the art of his first teacher, Marc Chagall, where the flight over the city and the life on the roofs perfectly accorded with the Vitebsk reality.

[quote style=”boxed”]From the Chagallian metaphorical ascent over side streets familiar from childhood, he was already within arm’s length of the systematized flights into the endless limits of Suprematist space. Malevich’s destruction of Renaissance perspective and the horizon line led to the revelation of another space—that of the boundless cosmos, which became the space onto which Lazar Khidekel would project his Suprematist compositions. Here, between sky and earth, having overcome gravity, geometricized structures were formed in weightlessness. Before becoming the volumes of futuristic cities above the Earth, these structures drifted into the status of space stations of earthlings.

It is this trajectory of Suprematist development into the cosmos and subsequent return to Earth, with a stop in the aerial city of the future, that determined the artistic and architectural development of Khidekel’s Suprematism. Because of the unique character of Lazar Khidekel’s extensive archive of surviving materials, all periods of his oeuvre are well documented through artworks, documents, and publications, as well as manuscripts and articles written by the artist himself. The archive enables one to study the stages of Khidekel’s Suprematist training at the Vitebsk Art School and UNOVIS (Affirmers of the New Art), including his early artistic education: drawing classes with Mstislav Dobuzhinsky, painting directly under Marc Chagall’s supervision (1918), learning the basics of architectural drafting and design in El Lissitzky’s architectural studio (1919–20), and one-on-one study of Suprematism with Kazimir Malevich himself (according to the UNOVIS questionnaire, he was the only student in Malevich’s “Dynamic” studio).

He quickly absorbed the Suprematist system, whereas most of the students never managed to cross the threshold of abstraction. In the Vitebsk Art School, there were only four students—Chashnik, Suetin, Chervinka, and Khidekel—to do so. Despite that fact, for Chashnik, referred only to Khidekel as a truly “revolutionary Suprematist.”2

As noted by Charlotte Douglas, one of the first and most important American scholars on Suprematism, these artists succeeded in further developing Suprematism in different directions. “Khidekel’s distinction was that this initial vision of Suprematist structures floating in space remained a central part of his art and architecture for the next forty years, and richly informed his later development as a professional architect.”3

The recent opening of the GINKhUK (State Institute of Artistic Culture) and GIII (State Institute of the History of Art) archives, combined with the publication of materials on Malevich’s legacy, have led to the appearance of numerous documents confirming Khidekel’s significant role in the development of Suprematism in his post-Vitebsk period.

In the second half of the 1920s, when Malevich returned to figurative painting, Khidekel continued his spatial odyssey into the clouds of futuristic cities. But even more important, throughout his whole life, he singlehandedly developed the pictorial-spatial concepts of Suprematism, anticipating the emergence of many avant-garde ideas and trends in Western art, design, and architecture, from which he was separated by the Iron Curtain.

S. O. Khan-Magomedov 1977 lecture on Khidekel’s futuristic cities4 aroused skepticism on the part of some of his colleagues, who remarked that if Khidekel was so much more advanced than Yona Friedman and the Japanese Metabolists of the 1950s, then he must be a genius. Today, Khidekel’s genius is verified by the words of Malevich himself. In late February 1927, before traveling abroad, Malevich left instructions concerning work on a “Suprematist filma”: “We need Khidekel to create an architectural design, but if there’s not enough time, let him take a shot from Petin for the film crew. We need to show the entire development of volumetric Suprematism in accordance with the sensation of the aerial (aero) type and dynamic.”5 Between 1925 and 1932, Khidekel arrived at his fundamental concept of the Aerograd, an aerial city on steel supports, elevated above water.

Khidekel was not the only one to envision designs for futuristic cities. Other artists did so as well, including some from Malevich’s circle. To see the difference between Khidekel’s designs and those of other artists, suffice it to recall Gustav Klutsis’s social utopia, Dynamic City (1922), an image of a city-planet “built by the hands of working people,” whose figures are “frozen” in the instant of the working process.”6 If Khidekel had ever placed a human figure into an architectural design, it would most likely have been himself and certainly have included a landscape.

[quote style=”boxed”]Khidekel’s aerial city was conceived on a human scale, and even in the mid-1920s was technologically viable. It was designed to promote a humane development of civilization, in which the individual and nature were equally important. Khidekel believed in harmony between humankind and nature, and regarded human culture and nature as governed by the same laws of natural forces. Stemming from his childhood appeal to the starry sky, Chagallian takeoff, and understanding of Suprematist composition as a living, self-evolving organism, Khidekel’s planetary vision always retained warmth and humanity. His skillfully executed pictorial-architectural sketches of cities of the future are dominated by different shades of green, infusing architectural design with a new dimension—the environmental—sadly absent from most futuristic utopias as well as the phantasmagorias of the twentieth century.

One of his students recalled that Khidekel regarded the architectural profession as a kind one, focused on protecting man. Air and the sun’s rays are the criteria of architectural structures, as he wrote in one of his first professional published articles, “Flat Roofing.” In this piece, which addresses the sanitary-hygienic conditions of contemporary cities, Khidekel presents the technological and economic arguments for the introduction of horizontal zoning. The young architect writes: “We need to point out that flat roofing provides additional courtyard space surrounded by fresh air and illuminated by sunlight, containing its own justification in the economic aspect.”7

Khidekel had already written about overcoming the contradictions between nature and civilization in his first manifesto. In 1920, the sixteen-year-old Khidekel, together with fellow UNOVIS member Ilya Chashnik, produced AERO: Articles and Designs.8 One of the first UNOVIS publications, AERO anticipated the release of Malevich’s Thirty-Four Drawings, printed in the same lithographic studios of the Vitebsk school.9 Indeed, AERO entered the annals of modern art as the first environmental manifesto. The very term “AERO,” coined by Khidekel, resonates with spatial modeling, from cosmic settlements, nebulae, and aerial cities (also Khidekel’s terms) to the actual layout of buildings and pictorial fantasies.

As early as 1922, Khidekel called his volumetric axonometric perspective in the form of an airplane Aero-Club. With respect to this “first truly architectural work based on Suprematism,” Khan-Magomedov wonders why Khidekel had the architectural skills that enabled him to build a “diametric axonometric perspective (i.e., based on the dimensions of one of the axes cut in half), which had not previously been encountered in volumetric Suprematism.”10

For him, the answer lies in the fact that Khidekel underwent professional training at PIGI (Petrograd Institute of Civil Engineers) in 1922. While remaining a member of GINKhUK, he collaborated with Malevich, leading Suetin, and Chashnik—none of whom knew how to render architectural perspective—create Architectons and Planits.11 Larissa Zhadova also notes, “The main assistant in Malevich’s architectural experiments of 1924–25 was L. M. Khidekel.”12 According to GINKhUK documents, Khidekel directed a laboratory of Suprematist architecture, developed programs, and left behind a unique description of the premises of the laboratory and models situated there.13

Khidekel defined the face of architectural Suprematism in 1926 when he created its first real manifestation—his Workers’ Club—which quickly achieved widespread visibility, appearing first on the pages of Western journals, and later in publications in Russia, as well.14 Khidekel became a famous architect while still a student—a phenomenon even more unparalleled than his early artistic achievements, including participating at the age of fifteen in an exhibition alongside masters such as Chagall, Kandinsky, Malevich, Rodchenko, Popova, and Exter.15

The cosmic and volumetric stages followed each other, revealing Suprematism’s form-creating potential. Thus arose a cruciform structure, the leading diagonal axis of which is a powerful line defining the direction of motion. Among the compositions of this type is Dissection of the Black Square; Khidekel regarded this as part of a body of motifs, including nebulas, concentric circles, the grid, and flying space stations, which he believed contributed to the form-creating system of Suprematism.

This apprehension of objectless space through a universal system of geometric forms was realized in a distinctive monochrome drawing style, different from Suetin’s and Chashnik’s colorful graphic idioms of those years, and, instead, anticipating the language of Minimal Art and computer-generated visualization.

[quote style=”boxed”]The diagonal-centric compositions of the early 1920s became a launch pad for Suprematist painting’s departure into three-dimensional space. The diagonal as an axis of motion, a runway strip, became the most important compositional element, one that we will again encounter in Khidekel’s competition entries of the 1950s–1960s such as his designs for the Tsiolkovsky Museum and the Budapest Theater; in industrial projects (Khidekel worked at GIPROMEZ [State Institute for Design of Metallurgy Plants] alongside his teaching at LISI [Leningrad Institute of Engineering and Construction]); in the designs of his students, who proudly described themselves as belonging to the “school of Khidekel”; and in the pictorial-spatial fantasies intended for the gigantic planes of modern structures.

In his review of the 1995 exhibition of Russian Jewish artists at New York’s Jewish Museum, Hilton Kramer wrote, “One of the most interesting artists is an artist few of us nowadays have heard of: Lazar Khidekel who was associated with Malevich’s Suprematist cirle in the 1920’s and later turned to architecture. A Suprematist Concentric Circles (1921) looks amazingly like a sketch for very similar paintings that Kenneth Noland produced many years later.”16

Kramer was not aware that Khidekel’s concentric circles are thermal zones dispersing from the Earth’s core, as we know from the artist’s remarkable 1920–22 drawings, accompanied by commentaries. The highly refined, diversely textured pastel palette of the 1921 masterpiece Concentric Circles relates both to Khidekel’s monochrome nebulas and cosmic structures, as well as to the Minimalist and Color Field painting that emerged decades later, particularly in the hands of Kenneth Noland.

Today, when AERO has rightly entered the annals of modern art,17 it is clear that its radicalism sharply differentiates it from the famous handmade books of the Futurists: the work of art was determined by the project and is accompanied by a typewritten text; do the sources of Conceptualism not lie in this striving to connect art, science, and philosophy?

The logic of avant-garde art of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries can be detected in Khidekel’s works. In addition to the artist’s foreshadowing of Kenneth Noland’s circles, other examples readily come to mind: Khidekel’s blue-painted figural monuments of the 1940s may be seen as anticipating Yves Klein’s blue busts, while the organic forms of Khidekel’s raised futuristic city, where right-angled corners unexpectedly round off and form part of an acutely modern aerodynamic configuration, reverberate in Zaha Hadid’s “Suprematist” forms. Creating his spatial-pictorial fantasies in the mid-1950s–1960s, Khidekel forecasted the spectacular enlargement in the size of contemporary paintings. Khidekel said that a person of the nineteenth century was a pedestrian who could grasp minutiae, but that in the quickened pace of the twentieth century, volumes are all that could be discerned from automobiles and planes, and that, as a reflection of visible space, the size of canvases would increase accordingly with time.

[quote style=”boxed”] Lazar Khidekel belonged to the core of that group of artists who managed to break through from one time to another, and from inner, Earthly space to the outer, cosmic space, a space that continues to provide inexhaustible possibilities for discovering new worlds in art.

Notes

1 Mark, Regina, and Roman Khidekel Archive.

2 Letter from Ilya Chashnik to Lazar Khidekel, March 22, 1922. Mark, Regina, and Roman Khidekel Archive.

3 Charlotte Douglas, “Unearthly Art: The Planetary View; Kazimir Malevich and Lazar Khidekel,” 2011, in Lazar Khidekel (1904-1986): The Suprematist Vision of the World (forthcoming).

4 S. O. Khan-Magomedov, Lazar Khidekel (Мoscow: Russian Avant-Garde Foundation, 2008), p. 24.

5 “Malevich o sebe: Sovremenniki o Maleviche,” I. A. Bakhar and T. N. Mikheenko, eds., vol. 1, 150 (Moscow: RA, 2004).

6 S. O. Khan-Magomedov, Suprematism (Мoscow: Russian Avant-Garde Foundation, 2007), 310.

7 Lazar Khidekel. “Ploskie kryshi,” Nauka i tekhnika (1928).

8 Lazar Khidekel and Ilya Chashnik, АERO: Stat’i i proekty (Articles and Projects) (Vitebsk: UNOVIS, 1920).

9 Lissitzky led the architectural and printmaking workshops that inspired Khidekel and Chashnik to create their first book, AERO. Khidekel also participated in the printing of Malevich’s 34 Risunka (Thirty-Four Drawings), as evidenced in the copy of the book signed by Khidekel. Mark, Regina, and Roman Khidekel Archive.

10 Khan-Magomedov, Suprematism, 473.

11 Ibid.

12 L. Zhadova, “Suprematist order,” Problemy istorii sovetskoi arkhitektury (Moscow) (1983): 37.

13 Irina Karasik, “Lazar Khidekel at GINKhUK (State Institute of Artistic Culture) and GIII (State Institute of Art History),” in Lazar Khidekel (1904-1986).

14 Khidekel’s student project Worker’s Club was published in Wasmuths Monatshefte für Baukunst (Berlin, 1927): 413; L’Architecture vivant (Paris) 2 (1928): 46; Sovremennaia arkhitektura, no. 6 (Moscow) (1927); no. 4 (1930); and dozens of other journals and books.

15 First State Exhibition of Local and Moscow Artists, Vitebsk, 1919.

16 Hilton Kramer, “Jewish Artists in Rubble of Tragic Russian Era,” New York Observer, October 2, 1995, 1.

17 Exhibition 100 Years of Concrete . . ., Haus Konstruktiv, 2010–11, curated by Dr. Dorothea Strauss.

Regina Khidekel, a Ph.D. candidate in art history, is the founder and director of the Russian-American Cultural Center and president of the Lazar Khidekel Society.

So what if names of cities in their splendor

Caress the hearing with their fleeting sense,

It’s not the city Rome that lives forever,

But the human’s place within the universe.

Osip Mandelstam

Translated by Alyssa Gillespie